The late 40’s and throughout most of the 50’s were seen as a period in which our existence from colonial workers towards citizen of the motherland made great strides. The ever long struggle of our people to attain full democracy within our lands began with the interest of the common man. There was a socio-economic climate of racism, colourism, imperialism, colonialism, economic inequality and general inequalities. The basic rights and liberties we experience today did not exist during the 40’s and 50’s. Understanding the development of our constitution as well as the people who were instrumental in advocating for democracy, internal self-government and eventually nationhood, is key for our national legacy. There should exist a civic duty and responsibility to value our constitution, our motherland, our people and our heroes.

The 1950 Constitution

(i) the 1921 Wood Commission

The Wood and Moyne Commissions took place in the 1920’s and 1930’s at a vital point of history. The Wood Commission took place during the Great Depression of the 20’s and the Moyne Commission took place in the 30’s and 40’s, mostly during the Second World War. In 1921, the Wood Commission recommended the increase in the appointed members of the Legislative Council as well as the introduction of elected members. These changes aided in bringing forth more elected representation to the legislative council. Unfortunately, there were little benefits to the common individual, as a vast majority of the Council was made of unofficial members consisting of 13 persons along with 7 elected and 6 appointed members.

The unofficial members were those nominated by the Governor. In a majority of situations, these unofficial members voted for what “the establishment” demanded (Spackman). These were the local aristocracy and plantocracy; or in other words, the colonial elite who were of European decent. As a result of this, Trinidad and Tobago during the colonial era was incredibly destitute as the needs of the elite were not merely prioritized but formed the core focus of the governmental agenda. Unemployment and poverty were rampant. Child labour was common. Workers had no rights at all and were not legally able to establish unions. Society in our nation before internal self-government was largely impoverished, though it possessed very valuable resources like petroleum (Williams p.228-230). Even though, politically, there was some improvement (for instance, local nationals could nominate themselves as candidates in the Legislative Council) there was not enough political power by elected members as their motions could have been vetoed by the unofficial and ex-officio appointed members.

(ii) the 1938 Moyne Commission

In 1938, the Moyne Commission report brought forth the similar socio-economic issues that continued to exist, especially given the 1937 labour riots that took place. Seeing that these problems would only persist, the report gave recommendation for political reform to be made (Spackman). The Moyne report also showed the continued absence of adequate healthcare and educational facilities as well as horrible living conditions. The same levels of poverty either continued or got worse from the 1921-22 Wood Commission report. The Wood report brought onto the political landscape the introduction of a new Legislative Council through the 1924 Order-in-Council (Spackman). This council introduced 7 elected and 6 appointed members. I maintained the ex-officio membership of 13 individuals. In the Moyne Report, the Order-in-Council was amended in 1941 to increase the number of elected members. Recommendation was also made for labour unions or organizations to be members (Spackman). In 1945, universal suffrage was introduced after the findings of the Franchise Committee in 1941, with the first elections under such system in 1946 (Spackman).

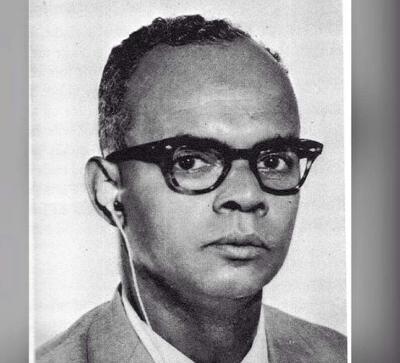

In the late 1940’s, there was a constant drive for internal self-government. As 1st Chief Minister, Albert Gomes, stated, “…it is truly impossible to produce truly representative legislation within a body that is not truly democratic” (Spackman). Even though Gomes was Chief Minister, there were still limitations with passing the necessary laws to develop the society. The Governor had the power veto any law despite a party or internal government having majority in the legislative council. Without haste, in December of the same year of being elected as Chief Minister, a select committee was established to bring forth reform. In 1948, the Report of the Committee on Constitutional Reform was made (Spackman). The report earned the disapproval of Dr. Patrick Solomon, a fellow member of the council, who saw it as a continuation of colonial rule within the legislative and executive council since the powers of the Governor, as well as three ex-officio members (the Attorney General, Financial Secretary and Colonial Secretary) were still directly involved in governance (Spackman).

Dr. Solomon made very harsh but fair criticisms of the overall report as it did not guarantee effective democratic principles as majority rule by elected officials. He suggested that the executive council should comprise of the elected majority and the Governor should only be an advisory role in domestic matters (Spackman). However, despite the protest by Dr. Solomon, his recommendations for a ministerial and independent government were not fulfilled. Through Order-in-Council of 1950, the majority report was adopted with various changes. These changes comprised of decreasing the unofficial members to 5 and gradually decreasing them. The Speaker of the Council would still be picked from someone outside the council but would not have the ability to vote.

Nonetheless, the executive council was led by those who were not the elected majority in the Legislative Council, so this proved to be a continuous flaw in the Order-in-Council of 1950 (Spackman). In 1955, there proved to be some hope for actual representation in executive and legislative councils. Despite Albert Gomes’ opposition to a select committee, he was later in favour of it, stating that people should go to the polls with a new constitution (Spackman). This was said even though Butler was against the committee report as there was a greater demand of democracy and representation needed. The Report of the Committee on Constitutional Reform of 1955 was much more progressive as it gave the legislative council the power to elect a Chief Minister who in turn was leader of the executive and legislative councils (Spackman). It is debatable whether the P.N.M would have been met with victory at the polls in 1956, with or without the Order-in-Council of 1955. Nonetheless, it is acceptable to say the order did provide ample environment for the development and success of the P.N.M. (Spackman).

Albert Gomes, 1st Chief Minister of Trinidad and Tobago (1950-1956)

Dr. Eric Williams, 2nd Chief Minister of Trinidad and Tobago (1956-1959)

Port of Spain, 1950s

References

- Williams, Eric. History of the People of Trinidad and Tobago. London, Andre Deutsch Limited, 1963.

- Spackman, A. (1965). Constitutional Development in Trinidad and Tobago. Social and Economic Studies, 14(4), 283–320.